Respected physician with a zest for life

Obituaries

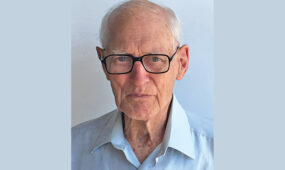

Dr Philip Harding AM BMedSc MBBS FRACP - Born: November 4 1941 | Died: May 25 2021

Dr Philip Harding AM was a cantor at the 9am Sunday Mass in St Francis Xavier’s Cathedral for many years and prior to that was actively involved in music and liturgy at Hectorville parish. His funeral Mass was conducted by Fr Pat Woods who had a long and close association with him, partly because, in Fr Pat’s words, ‘he knew he could beat me on the golf course’. Following is an obituary written for the Australian Medical Association SA.

Advertisement

Carpe diem’ (seize the day) was a leitmotif of the life of former medicSA editor, AMA(SA) president and endocrinologist Dr Philip Harding.

Dr Harding remained enthusiastically engaged with the South Australian medical community into his last weeks. He had an inquiring mind and a rare ability to see both sides of an argument – demonstrated by his approach to the age-old debate between road users. False dichotomies such as that between cyclists and motorists are a poor basis for policy, he explained as chair of the State Cycling Council to The Advertiser some years ago.

A keen cyclist, Dr Harding was also enthusiastic about motoring, taking regular forays into the South Australian countryside with medicSA partner-in-crime, Dr Robert Menz, to test the latest and greatest vehicles in the Adelaide market for readers.

This ability to see the world through another’s eyes, and describe it with a scholarly turn of phrase, also characterised his work as head of the Endocrinology Unit at the Royal Adelaide Hospital (RAH) and at AMA(SA), where he was a key player for more than 30 years.

As he noted in the RAH’s Foundation Day William Wyatt Oration in 2002:

‘Whenever we are confronted with a new, foreign or unfamiliar group of fellow human beings, the first step in developing understanding is to find some common ground. Those of us who belong to international medical associations take great joy in the bond of fellowship which exists between doctors and which transcends ethnic and cultural boundaries.’

And that is how Dr Harding came to advocate for Villawood detainee Dr Aamer Sultan, an Iraqi doctor seeking asylum in Australia, as enthusiastically as for improvements to rural medicine or public awareness of diabetes.

Those who knew him best agree that Dr Harding was not an easy person to categorise. As a respected physician, member of the Australian Health Ethics Committee, and ex-serviceman with the Royal Australian Air Force, he presented as a pillar of the Adelaide medical establishment.

Yet Dr Harding’s pathway to the Adelaide medical community was not typical of the time. Born in 1941 in Bedfordshire, England, Dr Harding lived in London with his mother until 1951, after his father, a naval officer, died as the HMS Penelope was sunk in 1944.

Advertisement

His mother remarried and the family emigrated to Tasmania in 1951, where Dr Harding was a boarder at Virgil’s College – an experience he found challenging as a 10-year-old immigrant. He moved to Hobart High School as a day boy before moving to Adelaide – initially to Salisbury North where his parents were teachers, and later to Adelaide Boys High School.

Clever at making things with his hands, a great singer and a talented pianist, Dr Harding may have taken a different path had he not been captivated at the age of 15 by the epic struggles of medicine as described by author Frank G. Slaughter in East Side General. After securing a number of scholarships, he went on to study medicine at the University of Adelaide while residing at Aquinas College from 1958, and joined the RAAF Undergraduate Scheme.

He met his future wife Rosemary McGrady, a member of the prominent Northern Territory pastoralist family, during a vacation in Alice Springs in 1960 and they married in 1964. Their union continued for more than 50 years, and included four children – Michael, Cathy, James and Stephen, and eight grandchildren.

The pair moved to Malaysia with the RAAF before a series of ‘medical misadventures’ beset their young family and caused Dr Harding to return to South Australia. He completed his physician studies at the RAH in 1970 and the family de-camped to London and Pittsburgh after Dr Harding won a Commonwealth Medical Fellowship for specialty training in endocrinology.

They returned when Dr Harding was appointed as a consultant endocrinologist at the RAH, becoming Head of Department and chairman of medical staff, developing a highly regarded unit with an outstanding record of external grants and engaging teaching. During this period, he also took great delight in performing in the RAH revues, including a highly acclaimed performance (dressed as a patient, complete with catheter bag) of The Impossible Stream.

He later contributed to the RAH diabetes centre, eventually becoming an emeritus consultant, and moving to private practice in 1997, becoming an external consultant to the Therapeutic Goods Administration on regulation of new medicines. He also retained an enduring relationship with the RAAF as a civilian consultant for clinical problems and on medical reclassification issues in the services.

Like Winston Churchill, whose prodigious body of work was based on an ability to survive on just four hours of sleep a night, Dr Harding preferred to use the wee hours of the morning to get things done. And also like Mr Churchill, he was prone to catching up on the zzzs in odd downtimes – including at the dinner table – which, he protested, was no reflection on the conversation prevailing at the time.

Ever busy – working, making things from wood, playing music, reading, playing golf (moderately he claimed), and advocating for the medical profession – he remained deeply embedded in the medical community throughout his professional life. A keen social organiser and traveller, Dr Harding rallied the troops for a regular medical fraternity ski trip, combined with professional development and established the AMA(SA) golf day.

As president of the AMA(SA) between 1990 and 1992, Dr Harding was particularly keen to expand membership and to campaign for improved health services in rural areas – and as medical editor of medicSA, he continued to work to bring the profession together.

Dr Harding lost his wife, Rosemary, to her third bout of cancer in 2017. In her memory he financed a garden at the back of Calvary Hospital for patients to sit in.

In 2018 he remarried after a four-month romance with Margie, a former Director of Nursing at the Memorial Hospital, whom he met at the closing day of the old RAH.

Both having recently lost a loved partner to cancer, the pair bonded over tea, conversation and a cheeky sense of humour. They travelled extensively until COVID clipped their wings and they entertained a lively passing parade of friends and colleagues – even during the last few weeks of his life.

Dr Harding is remembered as a thoughtful, lively, caring, clever person and a champion of the medical profession, of which he was proud to be a member. He also had a deep spiritual sense and was described by Margie as a ‘faithful servant’.

Comments

Show comments Hide comments