A sign of the times

National

The second and final assembly of the Fifth Plenary Council of Australia will be held from July 3-9 in Sydney. It is the first such gathering for the Catholic Church in Australia since 1937. What did the first four Australian plenary councils consider? What were the key issues the Church was facing at that time? The synopsis of the discussions and outcomes of previous plenary councils in Australia is captured from the comprehensive history prepared by DR PETER WILKINSON, originally published in The Swag and on the website Catholica.

First Plenary Council of Australasia, November 14-29 1885

While there had been earlier provincial councils, changes in the provincial structure of the Church in Australia meant all future gatherings would be plenary councils.

In 1884, Pope Leo XIII informed the bishops of Australia and New Zealand he wanted a ‘plenary’ council to be held within two years. He delegated the new Irish Archbishop of Sydney, Cardinal Patrick Francis Moran, to convoke and preside at it.

Advertisement

Cardinal Moran convoked the First Australasian Plenary Council on April 15 1885. The bishops of Australia and New Zealand were called and priests in each diocese were to elect one of their number to represent them at the council’s public sessions on matters concerning their own dioceses. Other priests, including provincials of clerical congregations, rectors of major seminaries, and selected theologians and canonists – acting as episcopal advisors – could also attend, but only with a consultative vote. Any lay men admitted could only act as a notary or advisor on civil law.

The council’s objectives were to emphasise the decrees of the First Vatican Council (1869-1870), to correct abuses in ecclesiastical discipline, to support and preserve Catholic education and to do whatever else might promote the salvation of souls and the good of the Church.

Cardinal Moran, who had attended the Maynooth Plenary Council a decade earlier, drew heavily from that gathering in preparing the schemata. Many of the draft decrees were new; others repeated decrees of the 1844 and 1869 provincial councils. The opening Mass at St Mary’s Cathedral drew 5000 faithful.

Eighteen prelates – none born in Australia or New Zealand – and 52 priests made up the Council’s members.

Significant effort went into planning new dioceses, vicariates apostolic, and ecclesiastical provinces. There was majority support for Brisbane and Adelaide to become metropolitan sees.

Cardinal Moran, who was determined to establish a major seminary at Manly, laid the foundation stone during the Plenary Council. It opened up a larger conversation about seminary training in Australia, but also the possible creation of an Australian seminary in Rome.

The gradual withdrawal of government funding for Catholic schools across the country meant Catholic education was a key topic at the Council. Four issues confronted the bishops: how to make Catholic parents send their children to Catholic schools; how to get the Catholic community to finance a Catholic school system; where the schools should be established; and how to find sufficient and suitable teachers.

A contentious issue at the Council concerned the governance of non-clerical (especially female) Religious. It centred on whether governance should be ‘diocesan’ or ‘central’ (ie not by the local bishop). Mother Mary MacKillop had insisted that central governance was essential for her congregation of Josephite Sisters. A vote of 14-3 went in favour of diocesan governance, which seemed to have settled the matter conclusively, but when the Holy See reviewed the decrees, it insisted that the decree requiring congregations of religious women be subject to the local bishop be suppressed.

Advertisement

Six decrees set out the future policy direction for Indigenous evangelisation. They stated that Indigenous peoples were capable of and willing to embrace Christianity, that land reserves should be set aside for them, that Religious congregations should be recruited to instruct them in religious and practical matters, that an annual collection for the Aboriginal missions be held in each diocese and that the bishops should protest against their persecution by the colonists.

The Holy See agreed that Brisbane and Adelaide be made metropolitan sees, that dioceses be erected at Grafton, Wilcannia, Sale, and Port Augusta, that the Vicariate Apostolic of Queensland be renamed Cooktown, and that two new vicariates apostolic be erected: Queensland for the Aborigines, and Kimberley.

After a review of the decrees by the Holy See, a total of 272, together with recommendations regarding the new territories, were approved by Pope Leo XIII in April 1887. The decisions on the new dioceses and vicariates came into effect with the Apostolic Constitution dated

May 10 1887, though the

Queensland Vicariate for the Aborigines was never formally erected.

The Council Fathers composed a pastoral letter to all the faithful to be read at Sunday Masses throughout the nation. It set out the new regulations and explained the principles on which they were based.

The letter urged Catholics to ‘better their station in life’, foster family prayer and set up ‘temperance societies’. It called for parents to acquire land which they could pass to their children and encourage their sons to acquire a useful trade or profession.

Second Australian Plenary Council, November 17 – December 1 1895

The Holy See granted approval for a plenary council, but said New Zealand’s bishops should not be invited because the Church in New Zealand was to be made separate from that in Australia.

All 72 Council participants were clerics: 23 prelates, all with a deliberative vote, and 49 priests (35 diocesan and 14 religious priests) with a consultative vote. Each participant was appointed to one of four committees: Faith, Discipline, Sacraments or Education.

Goulburn coadjutor Bishop Gallagher gave the opening address, stating that the Council’s aims were “to maintain the revealed truth, to condemn heresy, to uphold the uniformity and sanctity of discipline, to relieve the poor and battle for the oppressed, to advance the cause of science and knowledge, and to elevate mankind”.

Decrees were published on the further education of priests and the need for parish missions to be held every five years. A large number of decrees focused on the sacraments, including the religion of baptismal sponsors, having uniform rubrics for the Mass and other liturgies and the promotion of regular confession.

The discipline of priests was a major focus, including around financial reporting and the establishment of a union. There were warnings issued about priests’ consumption of alcohol and their choice of housekeeper.

Among the many decrees on Catholic education was a reaffirmation of the fairness of a pro rata share of taxpayer funding for students in Catholic schools.

The Council concluded on December 1 1895 with a joint pastoral letter denouncing secularism, the inordinate desire for wealth, and the weakening of family ties, and advocated a closer following of Christ, good family life with prayer and temperance, Catholic education and no mixed marriages.

The Council supported and launched a new seminary in Kensington NSW to prepare missionary priests for overseas ministry in the Pacific. It had been proposed by the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, who had arrived in Sydney in 1885 to establish a supply base for their missions in what is now Papua New Guinea.

Missionary outreach to and evangelisation of Indigenous Australians was discussed at length, as it had been in 1885 – albeit with little concrete progress having been made in the intervening decade. No new decrees were added to those passed in 1885.

The 344 decrees the Council passed were sent to Rome and reviewed by Vatican officials in late 1897. They were largely accepted, with recognition (approval) given in January 1898.

Despite the Council requesting seven additional dioceses – two in Western Australia, two in Queensland, two in Victoria and one in New South Wales – the Holy See would approve only one, Geraldton in Western Australia.

Third Australian Plenary Council, September 3-10 1905

In September 1904, Cardinal Moran requested the Holy See for approval to convene another plenary council and permission to invite the New Zealand bishops, who had expressed a desire to strengthen their unity with their Australian colleagues. When Pope Pius X approved the council, the New Zealand bishops were not mentioned, and were ultimately not invited.

In addition to the 21 Council Fathers, 12 superiors of clerical religious orders and 37 priest theologians attended the gathering at St Mary’s Cathedral. Once again, no lay persons were invited to participate. Three committees were established: Education, Discipline, and Faith and Sacraments.

It was agreed that the main work of the Council would focus on Catholic education, mixed marriage, ‘irremovable rectors’, priestly discipline, Catholic publications and missionary activity.

The 1905 Plenary legislated for a revised Catechism to be used in every diocese, and for a bishops’ committee to set new standards for religious education for all Catholic schools to adhere to, though they should follow the standards of state schools in secular subjects. The Council also called for each ecclesiastical province to establish a Catholic teachers’ training college for religious sisters and brothers.

The Fathers voted in favour of establishing institutions for mentally-ill and deaf males (they had already been established for females), promoting the publications of the Australian Catholic Truth Society, taking more care in the selection of books for libraries and promoting the Society for the Propagation of the Faith.

They voted against the publication of prayer and piety books without ecclesiastical permission, archbishops becoming a tribunal of appeal for questions of discipline and for implementing the decrees of plenary councils, a uniform tax for matrimonial dispensations, and having a summary and explanation of difficult words at the start of the catechism.

They also discussed the prohibition of sending Catholic children to state schools, the funding and care of sick, alcoholic and mentally ill priests, and Holy Communion for nuns. Evangelisation to Indigenous Australians was again an important topic for discussion, with the Council receiving updates from bishops in areas with large Indigenous populations. Among some bishops there appeared to be stronger interest in training priests to serve in foreign countries than among Indigenous Australians.

The 1905 Council was seen as a re-working of the 1895 Council, which had been, in effect, a re-working of the 1885 Council. All its new decrees were inserted into the earlier ones and set out in six chapters titled Faith, Ecclesiastical Persons, Sacraments, Discipline, Education, and Ecclesiastical Forum.

Pope Pius X approved the decrees on September 4 1906.

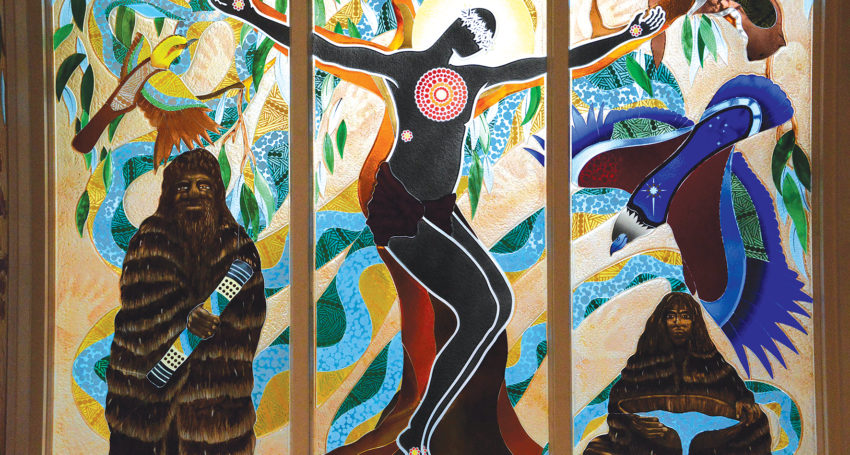

The Fourth Plenary Council held in Sydney in 1937. Source: Sydney Archdiocesan Archives Photographic Collection.

Fourth Plenary Council of Australia and New Zealand, September 4-12 1937

While plans to hold the first plenary council in two decades emerged in 1922, it wasn’t until 1937 that the Fourth Plenary Council was held. There were 32 Council Fathers present, including four bishops from New Zealand. Nine of the Fathers were Australian-born, but Irish prelates made up the largest nationality. Fifty-three priests were also members of the Council.

In anticipation of the Sydney gathering, a succession of Apostolic Delegates had worked closely with the Holy See in the preparation of 685 draft decrees in the schema. Many bishops accordingly saw the event as outside their control.

The schema’s focus was on clerical discipline, the selection of bishops and diocesan visitation and in responding to the 1917 Code of Canon Law. The bishops, on the other hand, were more concerned about common pastoral action.

During the Council itself, only small modifications were made to the decrees, and all would be approved. They included decrees on faith (doctrine), clerics, Religious, laity, the sacraments, sacred places and times, liturgy, teaching and education.

Pope Pius XI approved the decrees in March 1938 which were promulgated in March 1939, to take effect that September.

Some historians are critical of the perceived passivity of the Australian bishops in seeking to set the agenda for the Council.

The Fourth Plenary Council held in Sydney in 1937. Source: Sydney Archdiocesan Archives Photographic Collection.

In a pastoral letter following the Council, the bishops acknowledged much had changed since the previous council in 1905, including the establishment of an Apostolic Delegation and the hosting of Eucharistic Congresses in Sydney and Melbourne. But the main focus of the letter was the growing influence of atheistic Communism, its threat to the total subversion of Christian civilisation, and the need for ‘a sincere renewal of private and public life according to the principles of the Gospel’.

Related Story

National

National

High hopes for national gathering

Considered one of the most important decisions to emerge from the 1937 Council was the establishment of the Australian National Secretariat of Catholic Action which quickly established four separate organisations which would have a significant influence on Australian Catholic youth: the Young Christian Workers, the Young Christian Students’ Movement, the National Catholic Girls’ Movement, and the National Catholic Rural Movement.

Second Assembly of the Fifth Plenary Council of Australia

Livestream schedule – all times listed are local time (CST)

Sunday July 3: 4.30pm – Opening Mass

Monday July 4: 8-10.15am* – Opening Session

5.30pm – Daily Mass, celebrated in the Ukrainian Rite

Tuesday July 5: 8-9.15am*– Opening Session

5.30pm – Daily Mass

Wednesday July 6: 8-9.15am* – Opening Session

5.30pm – Daily Mass

Thursday July 7: 8-9.15am* – Opening Session

5.30pm – Daily Mass

Friday July 8: 7am – Daily Mass

8.30-9.30am* – Opening Session

Saturday July 9: 10am – Closing Mass

at St Mary’s Cathedral, Sydney (open to the public)

All livestreams can be accessed at www.plenarycouncil.catholic.org.au

Other content is available on the website and the Plenary Council Facebook page.

* End times are approximate, dependent on progress of proceedings.

Comments

Show comments Hide comments