Take fresh courage – share the hope

Opinion

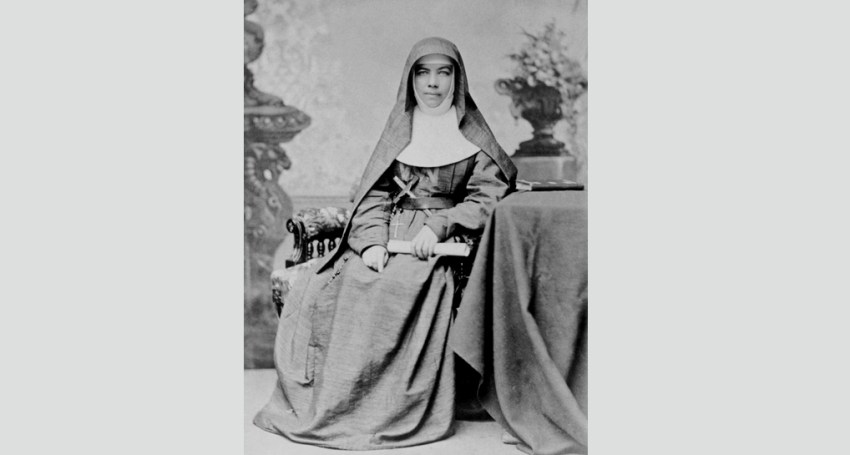

In 1902, at the age of 60, Mary MacKillop suffered a stroke. Her mind was unaffected and her speech intelligible, but with her right side paralysed, she had to make major adaptations to her life.

She now walked with a stick and, towards the end of her life, was eventually confined to a wheelchair. She dictated letters, but also learnt to write with her left hand and took up typing – the typewriter being at the time quite a new invention. She continued to govern the Congregation of the Sisters of St Joseph as Mother General and, over the next seven years, visited Sisters all over the country, opening up new works and responding to needs wherever she found them.

Advertisement

Certainly, we notice deterioration in significant aspects of Mary’s life as a result of the stroke. But we also notice enrichment. Having to depend more on others, she seems to speak and write words of encouragement more often. Her letters repeat what is at the core of faith and spirituality. She was in constant pain – she described it as being like a giant toothache all through her body – but she found deeper meaning in suffering as displaying in her own body the cross of Christ for our time (cf. Colossians 1: 24).

In this, the 10th year after Mary’s canonisation in Rome on October 17 2010, many people around the world have experienced the COVID-19 virus as a kind of communal stroke. We have been paralysed in some ways and have had to adapt to deprivations of all kinds. It is an unfamiliar world in which we carve out our future. There is a background fear in society.

We are challenged to find new approaches to life.

As in the case of any trauma, our first challenge is to come to grips with reality. Ignoring the situation won’t make it go away. In the process, we must, of course, take whatever steps are needed to safeguard our emotional and mental health. Accepting help if needed is part of this. When we are helpless, maintaining pride won’t help. I think of Mary MacKillop, a strong and independent woman, now having to have someone bathe, dress and feed her in the weeks following her stroke. People who have lost their livelihoods and have to depend on the charity of others can feel incompetent and resentful. We grieve with them as they adjust to their new situation.

An old adage says: ‘Failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts.’ We admire those who show courage. We give them bravery awards and recognise the qualities they display as they battle against the odds. ‘Character is formed in adversity’, they tell us. While all of this is true, those going through hard times often feel less than courageous. They just keep putting one foot in front of the other. It is only in looking back that we can acknowledge that something greater than ourselves kept us going despite the anguish we felt at the time. For Mary MacKillop, her trust was in a God whose love sees us through every evil: ‘Let us pray for the ever dear Will of our good God to be done, and in the end we shall see what peace and happiness will result from all our sorrows,’ she wrote.

Advertisement

When something goes wrong, our first instinct is to find information that will make us feel better. At the same time, nature reminds us that we are all inter-connected. For our own emotional health and that of society we need to identify the positive and take advantage of it. The picture of Mary at her typewriter can urge me to try the new in our time.

How many techno-ignorant grandparents delved into Zoom during the months of lockdown in order to remain connected to loved ones? The present situation calls us to explore paths untrodden in order to retrieve values that are timeless but whose existence is being threatened.

Mary MacKillop was in New Zealand when she had her stroke. What is noticeable in her story is the way so many people rallied to help her. The local bishop arranged for her to be taken from Rotorua to Auckland by train to which the Department of Railways attached a special invalid carriage and the doctor made the journey with her – all gratis. One of the Sisters wrote: ‘They took her up so gently from the bed to the ambulance, four priests carried her down very steep stairs, directed by the bishop and the doctor – and then on to the station, so gently.’

The ability to empathise with those who are suffering calls out the best in us. We think of the response of so many when tragedy strikes. Who could ignore last summer’s victims of bushfires? Yet we know that for some strange reason during this epidemic our society has, on occasion, brought a hostile attitude to the suffering of those on temporary visas, for example, and racism has reared its ugly head. Do we let compassion-fatigue make us less then human? Empathy with those who need our protection is required now more than ever.

Ten years ago we gave public recognition of God’s action in the life of Mary MacKillop, such that she could be held up as a model for all disciples of Jesus Christ. Her example reverberates around the world. Tapping into the Christian symbolism of the Cross enabled her to live into her post-stroke reality with courage, love and hope.

Our post-pandemic world will be different. Will we enter it aimlessly, or can we use this ‘time-between’ to identify what truly matters in life? What gives our lives meaning? Researchers already note that children confined to online learning now refer to ‘we’ rather than ‘I’ and have a greater appreciation of family than before. Yet even family cannot fully satisfy the ultimate yearning of our hearts. Where do we touch the depths?

‘Think of (Saint) Mary MacKillop and learn from her to be a gift of love and compassion for one another, for all Australians and for the world.’

Pope (Saint) John Paul II , Sydney, January 19 1995

Comments

Show comments Hide comments