Gizi's story a flicker of light in the darkness

People

Dr Ron Hoenig’s deep commitment to interfaith relations has its roots in German-occupied Hungary where his Jewish mother was protected by a young Christian municipal guard while her parents and four siblings were killed in Auschwitz.

I am alive today because of a young Hungarian man called Janos Zornansky.

With these words Dr Ron Hoenig began a moving account of how his mother, Gizella (Gizi) Berkovits, avoided the fate of 440,000 Hungarian Jews deported to concentration camps as he addressed members of Adelaide’s Jewish and Catholic communities at the annual Remembrance of the Shoah in St Francis Xavier’s Cathedral last month.

It was the first time Dr Hoenig, chair of the Australian Council for Christians and Jews, had publicly shared his mother’s story which she herself only told shortly before she died in 1997 at the age of 71. Gizi was one of tens of thousands of Holocaust survivors whose testimonies were filmed by Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation after he directed Schindler’s List.

Advertisement

“When Rabbi Shoshana Kaminsky asked me to speak I agreed because it’s a multifaith story,” he told The Southern Cross.

Gizi was one of eight children born into a poor, strictly religious Jewish family in a small town about 120km south east of Budapest. When she was 11 she went to live with her aunt in Budapest where she attended a Jewish school and then was apprenticed as a dressmaker.

At 16, she met and fell in love with Gaby, a 20-year-old Jewish man who was in a forced labour batallion with the Hungarian army. When the German army invaded Hungary in March 1944, Gizi was forced to wear a yellow star and feared imprisonment but a young municipal council worker, Janos, offered to help her. He provided Gizi with his sister’s birth certificate for a few days until he obtained a false identity for her.

Gizi at the age of 18

When the anti-Jewish laws worsened, he found her a place to board in a village one train stop from where he lived and accompanied her to and from her work in a factory every day.

As the Russians advanced on Budapest and the fighting intensified, it became too dangerous to go to work so Gizi went to live with Janos and his family. There were rumours of Russian soldiers raping women, so Janos hid Gizi, his sister and a neighbour in a small cellar where they stayed – day and night – for two weeks until they moved into an attic in the roof for a month.

At the end of the war Janos delivered Gizi back to her hometown where she found her brother who had returned from internment in Russia.

“Janos put his family and himself at enormous risk,” Dr Hoenig said.

“He was not alone; there were many of those ordinary humans to whom many of my generation of Jews owe their lives.”

Gizi’s younger brothers before their death in Auschwitz

After Janos took Gizi home, she was reunited with Gaby who had survived a labour camp and the Budapest ghetto. Like Gizi’s parents and siblings, his parents were killed in Auschwitz.

After marrying, the couple fled Communist Hungary and crossed through Austria – sometimes on foot – to Deggendorf, a displaced persons camp in Bavaria.

They remained there for two and a half years, awaiting resettlement, but lost patience and decided to try their luck in Israel, arriving around the same time it was declared a nation under the Balfour Declaration of 1948.

Advertisement

Gaby served in the army and Gizi was living on her own in Tel Aviv much of the time and struggling with the heat. She gave birth to Ron and they started making plans to migrate to the US or Australia.

“They weren’t very happy as neither of them were Zionists,” said Dr Hoenig.

“They were waiting for papers from my mother’s brother in the US or my father’s brother in Australia.”

The family was accepted into Australia first, despite the fact that there was a quota of 25 per cent on the number of Jewish refugees coming on each ship or plane after the war.

“The Australian Government didn’t want to let too many Jews in because we weren’t considered good farming fodder, there was quite a bit of anti-semitism,” Dr Hoenig explained.

“That’s why most Jewish refugees had to be sponsored by a family member or the community.”

The family sailed to Australia from Italy and Dr Hoenig turned two a few days before docking in Fremantle, then Melbourne, in 1952.

Despite living amongst other Hungarian Jewish migrants, they were not observant in the Jewish religion. Gaby was an atheist and didn’t accompany Dr Hoenig on the many Saturdays he had to go to the synagogue prior to the bar mitzvah, which he had “for social reasons”.

Ron with his parents at his Bar Mitzvah

His younger brother, Jeffrey, was born in 1961 and shortly after the family moved to “Irish-Catholic Richmond” where Gizi and Gaby ran a milk bar.

“Jeff grew up a lot more Australian than me and loves football and baseball,” Dr Hoenig said.

“I never really felt Australian and was drawn to the migrant Jewish culture, perhaps because my first language was Hungarian and I spent a lot of time in my early years with other Jewish migrants in St Kilda.”

While studying English and Politics at Monash University, Dr Hoenig became involved in the Labor Club and political demonstrations. His parents became “terrified I’d get into trouble” and sent him to stay with his aunts in New York where he completed a Masters in English. His thesis was on American Jewish novels in the 1930s.

After three years he returned to Melbourne and taught in schools but then decided to take up acting as a profession after dabbling in amateur theatre and “a bit of TV”.

A friend suggested he move to Adelaide and over the next decade he made a living out of his theatre work.

He first saw his wife Marion on a stage and over time the relationship deepened. Marion had three children from a previous marriage, and after their daughter, Sara, was born with a serious medical problem Dr Hoenig decided acting was no career for a father.

“We thought she was going to die…that put things in perspective,” he said.

After working in community arts at The Parks, he became director of the Multicultural Arts Trust and continued his interest in migrant cultures.

As for his connection with the small Jewish community in Adelaide, this was non-existent until a now healthy Sara decided at the age of seven that she wanted to attend Sunday school.

Marion was a lapsed Catholic and didn’t want her to go to a Catholic church so it was left to Dr Hoenig to take her to ‘cheder’ (Sunday school) at the Beit Shalom Synagogue on Hackney Road.

“That was a really huge experience, it was very powerful to go into the synagogue building and meet Jewish people and feel like I was in some way at home,” he recalled.

While Sara learnt Hebrew, attended cheder and made her bat mitzvah, she didn’t enjoy it. Now a mother and economist living in Brisbane, she doesn’t practise the faith but still regards herself as Jewish.

Similarly, taking Sara to the synagogue reignited Dr Hoenig’s “connection with Jewishness” rather than his “faith”.

“It’s complicated. My connection with being Jewish is essentially being part of the Jewish people and a Jewish culture and that includes religion, but I don’t have a very strong religious feeling,” he said.

Nevertheless, he became actively involved in the Beit Shalom community, including as administrator of the Sunday school and later president, and about

18 years ago he was invited to join the Australian Council of Christians and Jews (SA), of which he is currently co-chair with Catholic priest

Fr Michael Trainor.

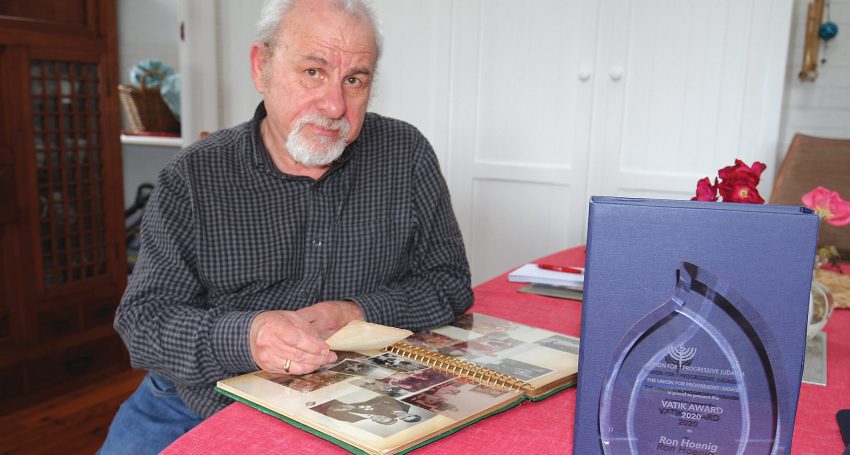

Last year he was appointed chair of the ACCJ and received the Vatik Award from the Union for Progressive Judaism (UPJ) for ‘past presidents of congregations and affiliate organisations who have continued to give excellent service and make a valuable contribution to their community and the wider community’.

Marion, who died two years ago, converted to Judaism in 2009. The couple travelled to Israel several times and Dr Hoenig said Marion was “much more Zionist” than him. They also visited Hungary and Auschwitz together.

Related Story

Visiting Auschwitz - a very personal perspective

He described going to the house where his mother grew up as “amazing”.

“We knocked on the door and walked into this house that was owned by Roma people and it felt like there were ghosts in this place, a presence,” he said.

Their trip to Auschwitz was both bizarre and emotional, as

Dr Hoenig described in a story he wrote in 2006. (read online at www.thesoutherncross.go-vip.net)

While he is adamant that anti-semitism and racism is very much alive today, he believes it is partly to do with religion but more to do with deep-seated phobias and demonisation perpetuated over centuries.

He is a staunch advocate for welcoming refugees like his family and expressed frustration at Australia’s hardline policies on asylum seekers, particularly among political leaders with a migrant background.

He said interfaith activity was “politically good because you create an understanding between people”.

“That’s a really positive thing to bring people of different religions together.”

His aim is to get more young people involved by encouraging “action” and using a similar approach to the interfaith climate change movement.

Having retired as a journalism lecturer with UniSA this month, the former editor of the Department of Education’s Express newspaper said he was determined to track down Janos’ two daughters.

Janos with his daughters

He suspects his mother kept in touch with Janos “a little bit” and that there was more to the story than Gizi revealed.

“I think he was in love with her,” he said.

Comments

Show comments Hide comments