A life of surprises

Obituaries

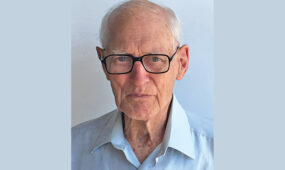

ARCHBISHOP MARK COLERIDGE, president of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference and Archbishop of Brisbane, looks beneath the public persona of Archbishop Wilson in this frank and powerful tribute.

At the end of a life that spanned 70 years, we try to see things whole, with the eye of God as it were, and to speak the truth of what we see, with the mouth of God as it were; and this is never simple.

Philip Wilson was not always what he seemed to be. He was a man of surprises, easily misread. It was no surprise however that the talented young Fr Wilson was sent to study canon law in Washington DC. Nor was it a surprise that a man of his personality revelled in much of what he found in America.

Advertisement

But then, out of the blue in 1996, came the call to serve as Bishop of Wollongong. That was a surprise. Philip hadn’t even finished his studies when appointed bishop; but he was appointed for a precise reason. Wollongong was in trouble, struggling to deal with the scandal of sexual abuse. In his last years, Bishop Murray before him had seemed overwhelmed; and the need for action from the new bishop was urgent. It required someone of Philip’s youth, energy and ability to meet the need.

His years in Wollongong weren’t many but they were tough; and because of what he did there he acquired a reputation of being compassionate, clear-sighted and determined in tackling abuse. At one point the Holy See decided against Philip and in favour of a priest accused of abuse. Philip made it clear that, if that decision were to stand, he would have to resign the see. He appealed the decision in Rome, won the appeal and stayed as bishop.

He went to Wollongong just as the first Church protocols on sexual abuse were appearing in this country; and he became one of the trailblazers in shaping the Church’s response to abuse in Australia, which was why in 2002 he was invited to speak to the US Bishops Conference on these issues. He was also a key figure in establishing the annual meeting of English-speaking Bishops Conferences to help each other better understand and address the reality of sexual abuse.

Another surprise came when, after only a few years in Wollongong, he was appointed Coadjutor Archbishop of Adelaide. It used to be said that you could move bishops from place to place but not from football code to football code. That was changing at the time, but Philip was very much a New South Wales rugby man. He could hardly have been more different from Archbishop Len Faulkner who was very much an Adelaide man. Len was the insider, Philip the outsider. Some thought he was a right-wing plant, hand-picked to undo all that Archbishop Faulkner had done in his years. That was never the case. Philip was no restorationist ideologue; he was a man of the centre, a pastoral pragmatist rather than some ideological warrior. Some who had hoped he’d turn Adelaide on its head were disappointed as the years told a different story.

Advertisement

There were those too who saw Philip as some kind of ecclesiastical bureaucrat. Yet the man I knew could be visionary. It was he who first suggested in the early 2000s that the time had come in Australia for some kind of national ecclesial assembly. Not all the bishops agreed, but Philip had sown the seed of what became eventually the decision to move to a Plenary Council. One sadness I feel as we bid farewell is that Philip didn’t live to see the assemblies of the Council and their fruit in the life of the Church.

There was some surprise when Philip was elected president of the Bishops Conference. He was a new Archbishop, and the Archbishop of Adelaide had never held the position. But he was a fine president through difficult times, three times elected to the position. This was because Philip could unify a conference in which there were tensions and disagreements. He could listen to all the voices, being both fair and firm. He had a strong sense of episcopal fraternity, often staying late to chat over a drink at night. And he knew his canon law.

But then came the inquiry which led eventually to Philip being charged, tried and convicted. It was surprise enough to us who knew him that he was charged, given his work to address abuse. But it was a real shock when he was convicted and given a custodial sentence. It was certainly a shock to Philip who through the long legal process had been confident of acquittal. Perhaps it was a shock from which he never recovered.

The pressure grew on Philip to resign, and he resisted with typical determination. He re-mained confident of vindication on appeal and hoped to return as Archbishop, even though his health had deteriorated badly. He was eventually cleared on appeal by a judge who described Philip as ‘a very honest and forthright witness’. Like others, I had come to see that, whatever the outcome of the appeal, Philip had lost the capacity to govern – because of his health, but also because at the time of his conviction cruel and unwarranted things had been said of him publicly, things that could never be unsaid. Very reluctantly Philip yielded to pressure and resigned, though that decision rankled with him, I think, till the day he died.

News of his death came as a surprise – not so much that it had happened but that it happened when it did. We didn’t expect it so soon. He simply slipped into eternity, almost unnoticed, on a warm Sunday afternoon. So much drama had swirled around him, but the end itself was undramatic.

Some may have seen Philip differently, but I found him humble and self-effacing. Usually when he rang me, he’d begin by saying ‘it’s only me’. When he chose an episcopal motto it was the opening words of Psalm 115: Non nobis Domine, ‘Not to us, Lord, not to us, but to your name be the glory’. As a personality he seemed confident and robust, but I found him in some ways shy and vulnerable. He may have seemed a complex character with a very complicated story; but it was his simplicity that struck me. I speak however as a friend who saw more of Philip Wilson than many. There was much more to Philip than his public persona may have suggested; and we see the more, so much more, as we give thanks for his life and bid farewell.

So now, Phil, dear brother and good friend, the greatest of all surprises awaits you as you stand face to face before God who has always seen you as you are and loved you, the God who says to you now at journey’s end: ‘Thanks for all you’ve done. Welcome home’.

Comments

Show comments Hide comments