What future for Christianity?

Opinion

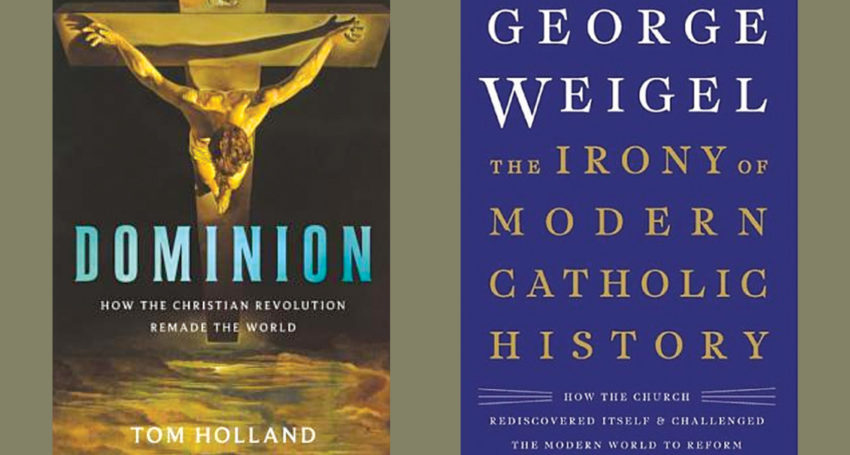

Book review - Dominion (Little, Brown) by Tom Holland (Little, Brown) and The Irony of Modern Catholic History (Basic Books) by George Weigel. Reviewed by Desmond O’Grady.

Tom Holland’s Dominion and George Weigel’s The Irony of Modern Catholic History raise queries about Christianity’s future by examining the past. Holland looks back at over 2000 years, Weigel has a narrower focus, just under 250 years, and confines himself to the Catholic Church.

For Holland, an English historian who was raised as an Anglican, Christ introduced the unprecedented vision of a god who identified with the poor. This produced a chain of innovations and revolutions aiming at greater justice and its underlying values still pertain in the Western world, he claims, even with people who revile Christianity.

Advertisement

He deftly recounts a wide range of episodes from the Persian empire of Darius to Harvey Weinstein and the Me Too movement which, according to him, would not have had force without 2000 years of Christian moral teaching.

Among his claims are that medieval canon law underlies the modern emphasis on human rights and that Christianity inspired the first stages of the French Enlightenment. Even if one accepted these claims, will this Christian influence persist in the future despite the decline in belief in the Christian faith throughout the West? Holland seems to think it will although he gives space to Nietzsche who insisted that without faith in Christ, Christian morality and culture would disappear.

Weigel, a prolific American Catholic writer, would not agree that Christian values will persist without Christ – one of his major preoccupations is that professing Christians may lose their place in the public square because of those who are hostile or claim religion is a mere private affair.

Weigel challenges the idea that Catholicism is contrary to modernity.

He argues that the Catholic Church initially opposed modernity, seeing it as a threat, but Pope Leo XIII (1878-1903) began what Weigel calls a revolution – dialogue with the modern world rather than condemnation. In other words, the Church has learnt from the long clash.

Some later popes reverted to a siege mentality but the Vatican Council (1962-65) embraced modernity. The majority were convinced that, from the Church’s experience and traditions, it could correct modernity’s shortcomings in the social, economic and moral spheres and reinvigorate certain values needed for functioning democracies.

Weigel says that by the end of the Vatican Council, the Catholic Church had completed a healthy renewal and was on the verge of a fruitful relationship with modernity.

But then there were two other revolutions – the sexual revolution of the late 1960s followed by accelerated globalisation with the expansion of internet and social communications, which abolishes space but confines many to an eternal present which wipes out the past.

For Weigel, in the Church at the moment there is not just a contest between progressives and those still opposed to modernity. Instead he thinks the reactionaries opposed to all change have lost because the Church did evolve as it reshaped the Gospel message, while staying true to it, for people in new situations.

Now the contest is between Catholics who want dialogue with modernity while retaining basic beliefs and those so enamoured of dialogue that they are ready to jettison beliefs.

Advertisement

He identifies two basic problems for the Catholic Church: the ‘challenging, puzzling and to some minds deconstructive pontificate of Pope Francis’ is one and the second is a green light for national episcopal conferences, such as the German Bishops, to take decisions opposed to the Vatican. (Of course there are other Catholics for whom Pope Francis is reviving the elan of the Vatican Council.)

Weigel does not respond to Pope Francis’ criticism of capitalism’s contribution to climate change. He deplores the clerical sexual abuse crisis.

Holland identifies the remaining elements of Christianity in a culture often indifferent or hostile to it while Weigel presents a Catholic Church which, he fears, because of new situations and the ‘puzzling’ pope’s policies, may miss the great opportunity the Council created.

Are these fears justified? This year’s Plenary Council of the Catholic Church in Australia can provide a measure of the degree of trust between clergy and laity which is needed to overcome fears about the Church’s future.

- Desmond O’Grady is an Australian journalist and author who resides in Rome.

Comments

Show comments Hide comments