Precious document in good hands

News

When Pope Pius XII decided to appoint Matthew Beovich as Archbishop of Adelaide, he did what popes before him had been doing for centuries and issued a papal bull – an official decree confirming in writing the appointment effective as of December 11 1939.

But as the diary of Archbishop Beovich attests, the document was despatched in a mail bag carried by a Dutch airliner which crashed in the sea near Java. The mail bag was the only item salvaged from the wreck shortly after and the cylinder containing the papal document was posted by the Dutch authorities to the Apostolic Delegate in Canberra. When opened, it was a ‘mass of pulp’, according to Archbishop Beovich, due to its long spell on the sea floor.

Advertisement

‘With drying and careful treatment,’ wrote Beovich, it was restored to ‘something like its former state and was easily decipherable with the Pope’s seal intact’.

After Beovich’s episcopal ordination and installation as Archbishop of Adelaide on April 7 1940 the papal bull was presumably stored in the Archives where it remained for the next eight decades.

As part of her routine assessment of items, Archdiocesan archivist Lucy Farrow decided to explore the possibility of conservation because of the bull’s historical value and importance to the Archdiocese.

The document had deteriorated to the point where the rolled-up parchment was unable to be opened and so she approached Artlab Australia for conservation advice and expertise. In a stroke of luck, the task was assigned to Roberto Padoan, the principal conservator of the Books and Paper department and one of the newest members of the team at Artlab. Not only is Roberto highly skilled in this type of conservation treatment, he also worked in the Vatican Secret Archives, as an intern first and then as a freelance conservator, for almost three years and then at the Nationaal Archief (Dutch National Archives) for 10 years.

“I couldn’t believe our luck,” said Lucy, who added that the Archives held the bulls of appointment for seven other bishops, including Adelaide’s first bishop, Francis Murphy.

Likewise, Roberto said when he came to Adelaide last July, the last thing he thought he would be working on was a Vatican document.

“That was really unexpected,” he said.

Roberto has worked previously on parchment documents, bindings and land maps of the 16th-17th century, while he was in The Netherlands, and on a parchment diploma of the 12th century by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I while he was at the Vatican. He said “the kind of things I saw there, you won’t see them anywhere else”.

“There isn’t another place like it…the Vatican has been an uninterrupted institution for centuries.

“Every king, emperor or government in the world was in contact with it – and the documents are still there.”

Scrutinising the damaged papal bull, Roberto explained how every element of the document – from the writing to the material to the lead seal – had been done with a strict procedure followed since the Middle Ages.

Advertisement

“Everything had to be unique and difficult to reproduce so people would know it was a genuine document,” said Roberto.

The parchment is made from animal skin and includes a lead seal featuring the name of the pope on one side and the embossed images of St Peter and St Paul on the other, to replicate the design of the papal ring. The term ‘bull’ comes from ‘bulla’, the Latin word for seal, this was the last element applied to the document by illiterates, preventing in this way alterations and diffusion of secret information.

Roberto said other heads of state would use gold seals to impress when communicating with the Vatican but the Pontificate preferred the cheaper metal of lead for what was known as the “seal of the fishermen”.

“I would see them in the Vatican, these seals that were sometimes half a kilogram of gold,” he said.

“On the other hand the Pope was sending these documents with lead seals, a much cheaper metal, but the importance of receiving a document from the Pope was immense – he didn’t need precious metal to show how powerful he was.”

Pointing to the clarity of the ink text on the parchment, Roberto said animal skin was the “perfect medium” on which to write.

The skin was submerged in an enzyme bath to make it easier to remove the hairs – that was done with a half-moon knife on a saddle-shaped tool and then it was stretched on a frame.

“While the parchment is drying on the frame the collagen structure reorganises itself and it becomes flexible, durable but at the same time rigid enough to write on,” he explained.

“It’s been done this way for thousands of years… some of the Dead Sea scrolls in Jerusalem that date back to the first century are still in an outstanding condition.”

The only problem is that the parchment reacts badly if it is wet or subject to intense heat because the skin wants to go back to the shape of the animal and loses the structure it had under tension.

The “gelatinised” edges of the Beovich papal bull indicate it has been exposed to high temperatures and will make it impossible to flatten the document completely.

Another challenge is the potential damage to the lead seal from air pollutants and a small crack in the seal, however, Roberto is confident that if properly encased it won’t worsen.

The document will be placed in a humidifying chamber to ‘relax’ the parchment then repair tears and infill losses and carefully tensioning it before mounting it on a rigid board.

The process can be repeated several times until it is in a state where the parchment can be stretched without damaging it. While the hands-on work will take at least a week, Roberto said it was difficult to predict how long the humidifying and drying process would take. He stressed that the aim of a conservator was not to try and make the document “look better” or exactly the same as the original because “its history doesn’t come only from the moment it was done but also form all the events that happened to it afterwards”.

“In this case, something terrible happened so if you remove all the damage, you remove part of its history.”

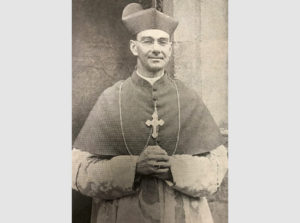

Archbishop Beovich at his consecration on April 7 1940. Source: The Southern Cross

Comments

Show comments Hide comments