Warrior for justice, teller of truth

National

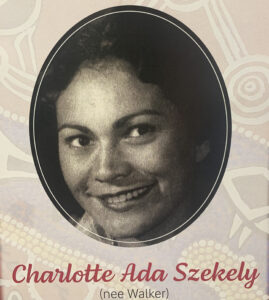

Charlotte Szekely (born April 7 1939, died June 17 1924).

The First Nations community in Adelaide and beyond is mourning the loss of black rights activist and founding member of the Aboriginal Catholic Ministry, Charlotte Szekely.

The Narungga woman who once led 40,000 people through the streets of Sydney to protest over black deaths in custody was remembered by her family and friends as a woman of “justice, love and wisdom” at her funeral service celebrated by Fr James McEvoy in Sacred Heart Church, Hindmarsh, on July 3.

Advertisement

Charlotte was born at Point Pearce on SA’s Yorke Peninsula, the eldest child of Anzac and Linda Walker. She had 14 siblings, seven sisters and seven brothers. Three brothers died as young children at Point Pearce. Another brother, Robert, died on August 28 1984 at Fremantle Prison. He was 25 years old. The cause of death was asphyxia resulting from compression of the chest which he suffered during a struggle with prison officers.

Growing up on the mission, Charlotte was taught by her dad to box to protect herself and her siblings. She also was adept at skipping, athletics, netball and bareback horse riding.

Renowned for her sense of humour, two of her four surviving sisters recalled nearly “choking to death” with laughter at Charlotte’s antics and her impersonation of comedian Benny Hill.

Despite only completing school to grade 7, Charlotte could read and write. When she moved to Andamooka at the age of 19 she helped the Indigenous miners and European migrants to speak English and count their money for shopping.

She met Les Szekely, a Hungarian migrant who travelled from the Bonegilla camp in Victoria to Andamooka in search of opals. The couple also spent time in Snowtown, where they were married, after Charlotte’s father was killed in a car accident and Linda was left to care for 11 children.

Charlotte and Les were married in Snowtown and moved back to Andamooka where she was highly respected as a counsellor to many and as an opal cutter. Her younger siblings often came to live with her, including Yvonne who remembered her sister advocating for the disadvantaged.

After Robert’s death Charlotte travelled to Fremantle for the inquest and when the prison guards refused to testify, she became committed to the campaign for a royal commission into aboriginal deaths in custody.

While representing the family on a campaign tour of Australian cities, she stood on the stage of Town Hall and bravely told her brother’s story in front of 1200 people. Sr Michele Madigan rsj was at the gathering and recalled how moved she was by the “absolute silence” as the names of the dead were rolled out on a big screen.

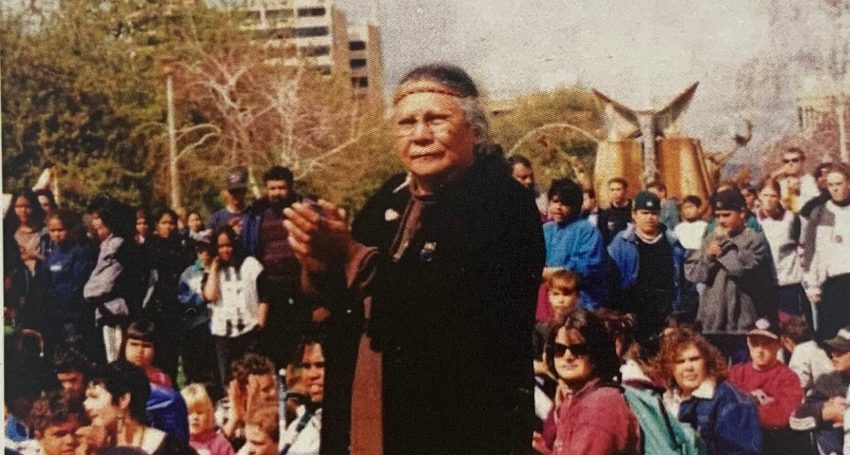

Returning to Adelaide, Charlotte helped establish the local Committee to Defend Black Rights and she could be seen at the front of marches and on the steps of Parliament House with a loudspeaker in hand, wearing her flowing skirt, long black coat and large cross around her neck.

Advertisement

At one of the first Adelaide gatherings in a packed Methodist Church, Franklin Street, Charlotte gave permission for a video of Robert singing one of his own songs, Solitary Confinement, to be played.

Sr Madigan said there was no doubt that it was only the pressure of large rallies and the constant call from families who had lost someone that resulted in Prime Minister Bob Hawke establishing in 1987 a royal commission into the deaths in custody of 99 Aboriginal men and women.

Grandson Tony Szekely said his first memory of ‘Grandma Charlotte’ was at a protest with a microphone in her hand and he thought she was a celebrity, especially after he saw her photo in the newspaper the next day.

But while she was labelled a “freedom fighter” and “activist”, Tony said she “really hit her strides” when she became a grandmother. When she came to grandparents’ day at his school – an hour-long event – she came for the whole day and taught the kids how to do Indigenous paintings and told stories, as well as making them laugh with her cheeky sense of humour. By the end of the day the whole class was calling her Grandma Charlotte.

During the funeral service, Charlotte’s sister Mabel, the second oldest of the Walker children, sang a song from their childhood days called ‘Help Me’.

Mabel’s son John Lochowiak, chair of NATSICC, proudly told of how his Aunt Charlotte had joined NATSICC in 1992, following on from her involvement in the Aboriginal Catholic Ministry and Otherway Centre in Pirie Street, Adelaide.

Charlotte’s faith and deep spirituality remained important throughout her life.

She was very proud of the fact she was born on Good Friday and was delighted when her niece gave birth to a son on Good Friday.

Despite continuing her hard work for the Aboriginal rights movement well into her 70s, Charlotte never received any recognition.

Yvonne said her older sister was “proudly black” even in her younger days when it wasn’t easy.

Fellow activist, Lisa, first met Charlotte at a protest in Adelaide in 1986.

“To me she was already a giant, I knew of her and her family, I knew of her fight and the work she was doing for black rights. I had a copy of her brother’s poems…we met at one of biggest marches I’ve ever seen in Adelaide and she was there at the front,” she said.

“She was a woman of justice, a woman of love, a woman of wisdom and someone who influenced my life incredibly.

“Her kindness and her love could fill the whole universe”.

She said even when the activists’ phones were being tapped and they were being watched by the authorities, Charlotte didn’t stop “demanding justice” and gave others the courage to do the same.

“She was a warrior for justice in that long flowing skirt, walking down the streets of Syndey, big cross around her neck, and that long black jacket.

“She commanded attention, her presence was immense. She never gave up on truth telling before it was a theme.

“She is the epitome of this year’s NAIDOC Week theme…she kept the fires of justice and truth telling burning when no one else did, she is ‘blak, loud and proud’.”