A life of giving herself to others

Obituaries

Sr Janet Mead rsm - Born August 15 1937 | Died January 26 2022

All things to all people. These words of St Paul are engraved on the ring Janet put on when she took her religious vows. They are words she lived by, never counting the cost that comes with trying to be all things to all people.

Two years before Janet’s birth her parents had lost their second child, Desmond, at the age of just six. From her early years Janet knew the fullness of her mother’s love, but she knew also the suffering in her mother’s heart, a grief that never left her.

Advertisement

Janet saw firsthand, at home, the suffering of refugees, when her mother Hannah opened her small house at Goodwood to a refugee family during the war years. Later she saw her mother visiting women in prison as part of her Legion of Mary work.

Janet emulated the example set by Hannah, supported by her father Bill and lived her life by giving herself, asking nothing in return. She made demands only on behalf of others. She gave her energy, her talents, her fire always for others.

She taught at St Aloysius College for about 18 years in two stints. In between she taught for six years at Mater Christi College at Mount Gambier where she was in charge of the boarders. She also taught at

St Mary’s Franklin Street for a year.

Many old scholars still remember the vitality, the life she gave to all her students, inspiring them, leading them, opening up their hearts, their minds and their souls to the new, to the best in music and drama, history, English, social studies, chemistry, maths and religious studies.

After school, sometimes with a couple of students in tow, she would dash through the convent, pick up a couple of slices of bread, slap butter on them and rush to music or drama practice.

In the early 1980s things changed. There were more constraints, there wasn’t so much space for the arts. She took time to consider and then embarked on a new career. She had long thought about ways to meet the needs of the homeless, some of whom would knock on the convent door asking for food.

Janet joined with fellow Mercy Sister Anne Gregory and planned the setting up of the Adelaide Day Centre for Homeless Persons, which soon became known as Moore Street. With no practical experience herself, she leaned on Anne’s social work background and the experience Anne had gained when setting up women’s shelters. Together they had a clear vision of the way people should be cared for: to welcome the homeless and the dispossessed, to find homes for them, to feed them and to provide, during the day, a home where they could feel the security of honest love and sympathetic understanding as well as meaningful work and a sense of purpose.

Advertisement

That is exactly what the centre has done since 1985. And with the help of so many people, the centre’s work has blossomed and borne fruit beyond even Janet’s imagination. The centre has changed countless lives, not only the lives of those who came seeking help but also the lives of those who came to help.

Janet was faithful. She was faithful in her love for her mother and father. She ensured that both of them had the best care when they needed it, her mother particularly, for whom she cared at home for 14 years until her death.

Janet was faithful to her vocation as a Sister of Mercy. She was among those who pioneered a new way of being a religious sister in the modern world. She turned preconceptions upside down; no convent, no habit, but a whole new way of living, of working, of praying, of engaging with the world, of extending the convent community into the wider world.

Janet was faithful to the Mass she started in the Cathedral in 1972 with the great assistance and support of Monsignor Robert Aitken, then Cathedral Administrator. The Mass started with a Cathedral packed with 2000 mostly young people every Sunday for several years. That Mass, in slightly altered form has continued every week for almost 50 years. The location has changed, the numbers greatly reduced but the essence is still there.

Janet lived life to the full. She considered herself lucky to have studied music at the Elder Conservatorium in the days of Professor John Bishop. As a student, one of her crowning achievements was to play Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with a full orchestra.

She was influenced by wonderful Mercy women such as Sister Carmel Bourke, Sr Deirdre O’Connor and Sr Monica Marks. They opened her mind to new frontiers in music, drama, literature and theology.

The 1970s ushered in the new musical works of the time; Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar. Undaunted by the timorous caution of many in authority in the Church, she saw these things as a way to teach young people to see God and the purpose of our lives in a new way. As time went on the Rock Masses led to connections with those working with oppressed people: Jan Gallagher in Ecuador; Rosemary Taylor, a lifelong friend who worked in Vietnam with the orphans of war; Brian Gore in the Philippines; and Jim Neeson, a Republican community leader from Northern Ireland. These encounters led to a deeper understanding of the Gospels. They also led to the fundraising, by means of the Romero Company plays, for projects such as the Good Shepherd Sisters in Nong Khai, Thailand; Sr Carmela in the Philippines; Sr Sally Duigan in South Africa; Sr Menggay and now Joy Balazzo in the Philippines.

The 1970s ushered in the new musical works of the time; Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar. Undaunted by the timorous caution of many in authority in the Church, she saw these things as a way to teach young people to see God and the purpose of our lives in a new way. As time went on the Rock Masses led to connections with those working with oppressed people: Jan Gallagher in Ecuador; Rosemary Taylor, a lifelong friend who worked in Vietnam with the orphans of war; Brian Gore in the Philippines; and Jim Neeson, a Republican community leader from Northern Ireland. These encounters led to a deeper understanding of the Gospels. They also led to the fundraising, by means of the Romero Company plays, for projects such as the Good Shepherd Sisters in Nong Khai, Thailand; Sr Carmela in the Philippines; Sr Sally Duigan in South Africa; Sr Menggay and now Joy Balazzo in the Philippines.

All this might lead you to think that Janet was an enthusiastic lover of life, a musician, a singer and a teacher. She was all of that but she was much more: Janet developed a blazing bonfire of outrage against injustice. She could be incandescent, white hot with fury when the situation required it. But it was never for herself. Her anger blazed when those she loved were mistreated or dealt with unjustly.

When her students were not being taught properly she spoke her mind. She listened to the stories of those who came to the Centre, she went out on the streets, she got on the phone, she went to people’s offices to fight for Aboriginal people, for refugees, for the victims of harsh government welfare policies, for the East Timorese during the Indonesian occupation, for black South Africa during apartheid, for the people who would become the victims of the pokie machines when they were introduced. She fought against the City of Adelaide dry zone which to this day unfairly targets Aboriginal people.

The words of Dylan Thomas were a favourite: Rage rage against the dying of the light, do not go gentle into that good night.

But her raging was not idle, reactive fury: she agonised over her decisions to involve herself in causes perceived to be unpopular.

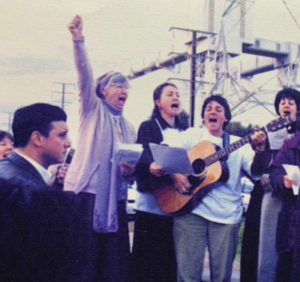

She was essentially a shy person, but she overcame her shyness when the needs of others required it. She was there when Howard and Corrigan tried to break the union, not just singing at the picket lines but organising the delivery of soup to the workers. She was there at 3am trying to block the first trucks carrying uranium from Roxby Downs in the 1980s. She was there on North Terrace last year, drawing attention to the scandalous treatment of Julian Assange for his alleged crime of telling the world the truth about American air strikes on Iraq.

She was essentially a shy person, but she overcame her shyness when the needs of others required it. She was there when Howard and Corrigan tried to break the union, not just singing at the picket lines but organising the delivery of soup to the workers. She was there at 3am trying to block the first trucks carrying uranium from Roxby Downs in the 1980s. She was there on North Terrace last year, drawing attention to the scandalous treatment of Julian Assange for his alleged crime of telling the world the truth about American air strikes on Iraq.

She lamented for the Palestinian people for many years and especially during the Israeli bombing of Gaza last year. All of that feeling went into her beautiful singing of one of the songs in our play supporting the Palestinians just four months ago.

She grieved for the people of Burma and the failure of the Australian Government to call out the military coup.

So many scenes of injustice, so much anger, so many tears.

But there were reasons to celebrate too, times when justice prevailed: Nelson Mandela’s release in 1994 (she met him briefly in Melbourne); independence for East Timor although at great cost; the Mabo case exposing the truth about Aboriginal dispossession; the Syrian people resisting Western and terrorist attempts to overturn their elected leader; the canonisation of Archbishop Oscar Romero; the election of Pope Francis and his focus on the poor and the need to care for the earth; the recent opening of the Centre’s home for Aboriginal people released from prison; and the election of the progressive government in Chile.

None of it is enough but these victories gave her just enough hope to carry on the fight.

On a more down to earth level, she rejoiced in Sturt’s five premierships in the 70s; the Crows’ two in the 90s and Andrew McLeod’s two Norm Smith medals; Eddie Betts’ magic; Ash Barty’s triumphs and the Ashes victory with Scott Boland’s spectacular debut.

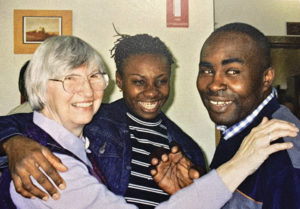

Perhaps Janet’s greatest gift to the world was her ability to bring out the best in people, to somehow communicate with so many different people on a deeply personal level without being intrusive or judgemental. People came away from their encounters with her feeling better about themselves, better able to deal with the evils of the world, comforted if necessary, challenged to do better if that was required. She had a way of knowing people at a deeper level without apparently needing much time to do so. She wept with those who wept, mourned with those who mourned, railed against injustice with the oppressed.

Perhaps Janet’s greatest gift to the world was her ability to bring out the best in people, to somehow communicate with so many different people on a deeply personal level without being intrusive or judgemental. People came away from their encounters with her feeling better about themselves, better able to deal with the evils of the world, comforted if necessary, challenged to do better if that was required. She had a way of knowing people at a deeper level without apparently needing much time to do so. She wept with those who wept, mourned with those who mourned, railed against injustice with the oppressed.

As we mourn the loss of Janet’s footsteps beside us, we know that, as Sr Ruth Egar rsm said, she is ‘still here’. She is here in all of us.

She will be with anyone who strives for justice and fairness and who tries to make the lives of other people better. She will be that persistent voice in the consciences of the powerful, reminding them of the plight of those she loved: the Aboriginal people, refugees, the poor and the homeless. She will be with all people who strive to help others bear their burdens, who choose to be fully alive compassionate people, who choose to try to be all things to all people.

– Taken from the eulogy given by Sr Janet’s nephew Greg Mead on behalf of the Romero Community.

Comments

Show comments Hide comments