A fine man with a gentle spirit

Obituaries

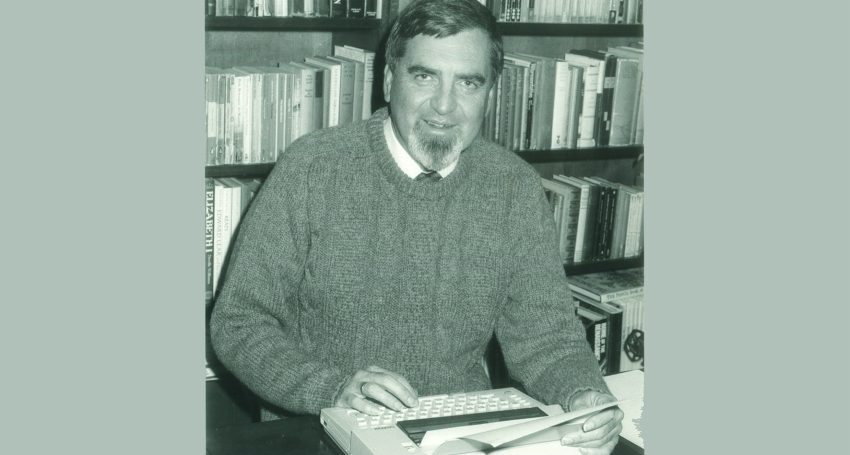

Deacon Nicholas Gregory Kerr - Born: March 26 1940 | Died: July 27 2021

How should we remember Nicholas Gregory Kerr?

A friend may have provided the perfect epitaph just hours after he died.

‘A fine man with a gentle spirit,’ the friend said.

Nick, to use Abraham Lincoln’s phrase, put his trust in our ‘better angels’.

He didn’t preach. He didn’t moralise. As Aeschylus wrote 2500 years ago, Nick believed wisdom would come to us, drop by drop, through the grace of God.

Advertisement

He was, in short, blessed by faith.

Nick believed truth and justice would prevail through the greatness of God – but not through some roll of thunder coming from above and a flash of lightning, but the greatness of God inspiring the goodness of his fellow men and women.

And that greatness, he believed, was best expressed by service.

Nick served God by serving his fellow men and women and served his fellow men and women by serving God.

There was no one or the other.

For Nick, the two were inextricably linked – the one and the same.

And so he made his life a life of service.

Nick must have stood out as a young man.

It’s hard to imagine many of his contemporaries at the end of the fifties sporting a beard, riding a good, gutsy Honda 750 – and having a grand piano shoehorned into their bedrooms.

He spent a stint in a seminary, but that was not to be.

He attended the Conservatorium, but never finished a degree.

That love of music, however, led him to meet the love of his life, Eveleen, and to almost 60 years of the strongest marriage.

And the stirrings of change around this time led Nick to become involved as a member of the State committee for the ‘yes’ campaign in the 1967 Aboriginal rights referendum; the most overwhelmingly supported referendum in the history of the federation and part of a lifelong commitment from him to the cause of Indigenous people.

This, in turn, led to a crucial decision that would dictate his career.

He had felt that there were already too many journalists in the family, but settled into a role with The Southern Cross newspaper.

He realised just what could be done by telling stories.

God tells us in Proverbs to ‘speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves’ and in Isaiah to ‘learn to do right; seek justice’.

Advertisement

That is just what journalism enabled Nick to do.

He was always involved in the life of the Church and the Cathedral parish, but pursued his main mission through the media.

His efforts were recognised.

He won countless awards for his efforts and was offered roles in Rome and elsewhere overseas – even, at one stage, a partnership in a major public relations firm.

But Nick stuck to the work he had here.

And far more important than any professional accolades or job offerings was the recognition he received in 1981 when he was awarded a Knighthood in the Order of Saint Sylvester by Saint John Paul II.

A firm believer in ecumenism, it was an honour for Nick to pursue his mission with, briefly, the Anglican, and then for almost 20 years, the Uniting Church.

And it was during that last period that the most extraordinary chapter of his life began.

In the middle of the nineties, his eye for a story led him to some of the first African refugees in South Australia, people from Sudan – the horrors they had suffered in their homeland for their faith and ethnicity and the challenges (and, yes, prejudice) they faced in their new home.

His thirst for justice created an unbreakable bond with the people he met.

African visitors to his home became not just members of the household, but family.

In 1998, Nick worked with the World Council of Churches’ communications team at the World Assembly in Zimbabwe.

That was only a jumping off point.

Afterwards he went to Nairobi to meet Sudanese refugees.

On other visits to Africa he spent time with refugees in the Nairobi slums, in the Kakuma Refugee Camp and in displaced people’s camps.

By this stage he was in his late fifties but that didn’t deter him. Nor did the very obvious danger he faced.

To deepen his understanding so he could serve better, Nick ventured into Sudan with members of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, a terrorist group in the eyes of the Sudanese regime.

If captured, one can scarcely imagine the fate that may have awaited him at the hands of the government that was then sheltering Osama bin Laden.

It was a truly extraordinary demonstration of not just courage, not just moral courage, but of the strength of Nick’s commitment to faith and service.

God watched over him, kept him safe and the last chapter of his life continued and became yet richer.

He retired in a formal sense, but continued to devote his life to the African community and, so he could serve more widely, started to study towards the Diaconate.

He was ordained in 2009.

He served as chair of the Australian National Association of Deacons and a delegate to the International Diaconate Centre.

However, what would have delighted him more was the joy he gained from serving the Church in a new role and the joy he witnessed at weddings and baptisms and events such as the blessing of his much beloved Lucia’s Pizza Bar at the Central Market.

He also gained a special joy from the greater involvement the Diaconate gave him with his African friends, being able to officiate at the African Mass as well as advising and advocating for the African community.

As mentioned before, Nick was a strong believer in ecumenism and served as the chief executive of the Diocesan Ecumenical and Interfaith Council.

In this role he found inspiration and support, particularly from friends such as Rabbi Shoshana Kaminsky from the Best Shalom Synagogue here in Adelaide. It was a privilege for him to assist in his own small way with the founding of the Adelaide Holocaust Museum.

Nick didn’t moralise, although he had a firm moral compass.

In the eighties, at a time when same sex-attracted people faced a new wave of persecution with the fear of AIDS, he showed nothing but love and understanding to his children’s gay friends, many of who had not only been rejected by their own families, but even expelled from comfortable and relatively privileged homes.

They were all worthy of love and respect in Nick’s eyes.

Nick’s wit, his humour, his sense of mischief and his delight in nonsense, his creativity, his love of beauty and knowledge, the simple joy he took by refreshing his mind with a walk and enjoying what he found around him, let alone his affection, made him such a joy.

Nick told this newspaper back in 2017 ‘I wanted to do something worthwhile’.

He did much, much more. He did something remarkable.

Less than three weeks before his death Nick prepared a video message on the traumatic background of a young African to be presented as a formal court submission.

He would have thought his mission was simply on hold when he contracted his final illness.

So, what message do we draw from the life of Nicholas Kerr?

What would he have wanted us to learn?

More importantly, what would he want us to do?

Lincoln said: ‘Let us have faith that right makes right and in that faith let us to the end dare to do our duty as we understand it.’

Nicholas Kerr would emphatically agree.

Nick’s grandson described him as ‘always a strong believer, helped everyone he could and was a good man’.

A fine man with a gentle spirit indeed.

We give thanks to God for the life and love of Nicholas Kerr.

And may his memory be a blessing.

– Taken from the eulogy by Nick’s son, Christian Kerr

Comments

Show comments Hide comments