Opening up conversations on domestic violence

News

In late September this year, about 20 people signed up to attend an evening meeting at St Augustine’s Church in Salisbury.

Only a handful showed up but the guest speaker, a lawyer from the Attorney-General’s Department in Adelaide, was unconcerned.

“It doesn’t matter,” Chol Pager said. “I am pleased if there is one person we can help.”

Chol was there in a personal capacity but “with a professional lens,” he said. He is not a social worker, a child welfare officer nor an expert in the child protection policy but has a vital role to play.

Advertisement

The meeting at St Augustine’s – there was also one in May – was a forum for people facing domestic violence and for others wanting to help victims perhaps uncertain about attending themselves. It was also a chance for people to find out just what domestic violence entails and how to navigate a way through it.

Helping raise awareness around domestic violence and child protection – which often happen in tandem – is a must, said Chol, who begins his talk with the very basics.

“People don’t know how to react when a random government worker shows up at their house. It’s about showing them how not to react negatively when asked questions,” he told The Southern Cross.

“We talk about child protection and the law and how decisions are made and how the government can come into peoples’ lives.”

Most attendees are middle aged and a mix of recent migrants and more established Australians. Chol gives a PowerPoint presentation but the mood is deliberately informal and everyone gathers around to listen.

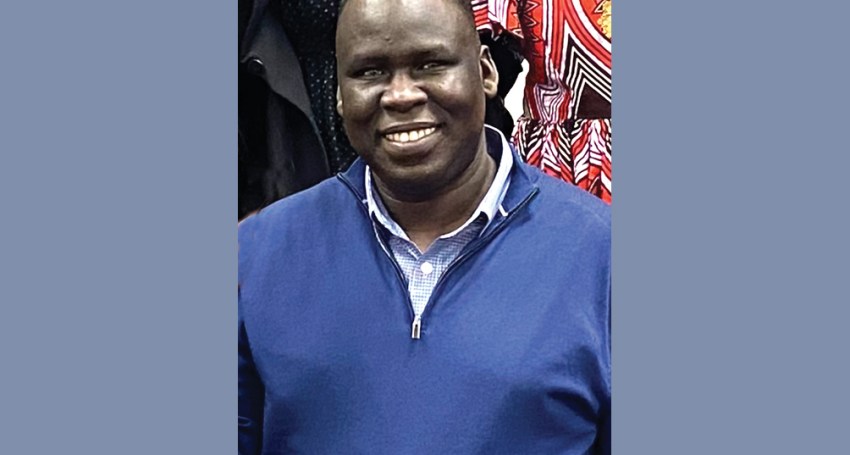

The meetings are the brainchild of pastoral support worker Clement Kuek (pictured) from the Archdiocese of Adelaide.

Chol, a former student at Nazareth Catholic College, remembered the Mary MacKillop dictum ‘Never see a need without doing something about it’ and when Clement asked Chol to help out, along he came.

“People are surprised about what constitutes domestic violence,” Chol said.

“Society has changed a lot from the traditional family and its gender roles. Coercive behaviour, legislated in May this year, is now a criminal offence.

“People think (in terms of) physical abuse and might not think about other forms of domestic violence.”

Outcomes too can often extend beyond the immediate victim. If financial support disappears or the breadwinner is taken away, any children will likely suffer.

Then there is the guilt that a victim might feel in making a complaint and that someone might be taken away accordingly.

“For a long time the victim will be entangled,” Chol said. “It might take years for them to see this is not the norm.”

Advertisement

The practical impediments in getting people to come forward when faced with domestic violence are many, said Chol.

The stigma of being seen as a victim of domestic violence aside, for recent migrants there is uncertainty over the right to live in Australia and that can bring further subjugation.

“Lots of migrants might be here on visas and can’t speak up,” Chol said.

“This might be used against them by their partners and can put them jeopardy.”

Language can be another barrier to migrant communities in that victims can feel unable to voice or articulate concerns. Culture shock plays its part also.

Where you come from might not be the same as here and negative behaviours may have become normalised, Chol said.

“How will the rest of the community react if you are speaking up?” he added.

The St Augustine’s presentation included a list of community organisations and NGOs on hand to assist victims of domestic violence. Chol’s task is to raise awareness and point people in the right direction, to be a starting point.

“There is only so much you can do without giving legal advice,” he stressed.

“There are things you can’t control. You don’t want to overstep. It’s about opening peoples’ eyes to what domestic violence looks like.”

Opening up a mainstream conversation about domestic violence is imperative, said Chol.

“Schools don’t raise it. It needs to be covered. They talk about sex education and about consent but not about domestic violence. There is a need to explain to them how systems work.”

He said priests could also be a voice for raising awareness.

“Domestic violence is a huge issue and if people are not talking about it, where else do we go?” Chol asked.

Catherine House and Centacare are examples of Catholic agencies doing a very good job according to Chol but there needs to be more.

And it starts with talking about it.

The challenges are many. Not reporting systemic abuse within the household is common while engagement with the police is not always seen as a positive Chol said.