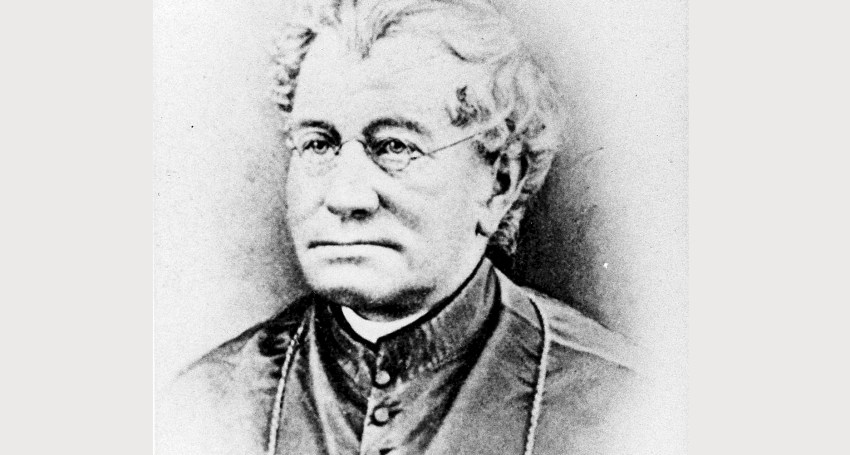

Honouring Adelaide’s first bishop

Obituaries

November 6 marks 180 years since the first bishop of Adelaide, Bishop Francis Murphy, arrived in Adelaide.

Bishop Murphy came to Adelaide when there was no Catholic church, school or presbytery and only one priest to assist him.

He set about tirelessly raising funds to build churches and schools. A staunch defender of the Catholic faith, he was described as ‘an eloquent, saintly man, a good horseman, and a capable musician’ by the Hon WJ Denny MC in The Southern Cross of June 16 1939.

Born in Navan, County Meath on May 20 1795, Bishop Murphy studied at Maynooth College and was ordained a priest in Dublin. He was appointed to St Patrick’s Church, Liverpool, as part of the ‘English mission’.

Advertisement

Denny wrote that it was a ‘fortunate accident’ that brought the Bishop to Australia.

Dr William Ullathorne happened to pass through Liverpool and persuaded Fr Murphy to offer his services to the Australian mission, arriving in Sydney in July 1838.

Dr Ullathorne had visited Adelaide in 1840 and was appalled by the harsh environment here. To his dismay he was appointed first Bishop of Adelaide in 1842. He begged to be spared from such a trial. The task of establishing the diocese then fell on the shoulders of Fr Murphy.

‘His zeal and eloquence received deserved recognition and he was rapidly appointed Vicar General of the Diocese of Sydney,’ wrote Denny.

He was ‘literally idolised’ by the people of Sydney and many were surprised he should be sent to ‘such an unimportant place as Adelaide’.

His time in Adelaide was described by predecessor Archbishop Christopher Reynolds as ‘an arduous one. His congregation was struggling. He had no help from the State, no church, no school, no home. An old cottage that was used as a public house became his episcopal residence. An old store was hired and fitted up as his cathedral, and here he commanded his self-denying labor (sic) as Bishop of Adelaide’.

Bishop Murphy’s first address to his people in November 1844 included the following:

‘Never let any difference in climate, in color (sic), or in creed interrupt for a moment that holy affection and charity towards each other so emphatically insisted on by the Common Father of all; and whilst you must live prepared to offer up to God, if necessary, the sacrifice of your lives, rather than part with the least portion of that faith which the Apostles and Martyrs have bequeathed to you with their blood, be ever ready to make the greatest allowances for the opinions and prejudices of your separated brethren, the majority of whom, as I know by experience, are opposed to you only because they never yet had an opportunity of beholding your religion in its spotless purity and beauty but only through a cloud of erroneous publications and the darkest mist of misrepresentation.’

The Census of 1844 puts the number of Catholics in the Adelaide Diocese at 1273. Drawing from Cardinal Moran’s writings on Bishop Murphy in his History of the Catholic Church in Australia, it is said that Bishop Murphy ‘knows every member of his flock by name, and nobody in the Catholic fold or outside of it hesitates to go to him for advice or material assistance’.

‘He attends sick calls. When he is not on the trail he is to be found in the church, which he succeeded in building, the work was begun in 1845 – or among his poor in the hospital, or teaching his children in the school which he erected within a year of his appointment to Adelaide.’ (The Southern Cross, November 13 1936)

Advertisement

Yet he managed to spare a few moments to play the piano and train a choir of which he was very proud.

In 1851 the Catholic men of the Diocese began to leave for the gold fields of Ballarat. Almost overnight the ‘Bishop’s flock’ had deserted him.

He knew they would return one day so he planned to follow them and attend to their wants but his Vicar General, Fr Michael Ryan, offered to go in his place. In those difficult times Bishop Murphy was offered another diocese but he preferred to stay in Adelaide.

In 1858 he returned from a trip to Tasmania, where he was called to ‘advise in matters of serious moment’ and became increasingly unwell. For two months he lay on his bed and on April 26 1858 he was called to eternal life.

On the morning of his death most of the clergy came into Adelaide. He sent for them one by one, spoke a few words of consolation to each, and told them that the end was near. They were all present when he passed away.

Permission was granted for him to be buried within the city square mile – the only other person given such an honour was Colonel William Light. His tomb lies beneath the sanctuary of St Francis Xavier’s Cathedral.

When his casket was laid at St Patrick’s Church, ‘nearly every person in Adelaide and those from far away came to pay their respects’. There was a long line of carriages drawn up at West Terrace waiting to deposit visitors at the church door. It was arranged that the church would be closed at midnight, but that was impossible as the crowds still remained.

His funeral in St Francis Xavier’s Cathedral the next day also attracted a crowd so great that ‘with much courtesy and firmness the police succeeded in ordering the people who were so anxious to pack the little cathedral’.

A chronicle of the time referred to the funeral cortege as ‘the largest that had been seen in the colony, and was attended by all the leading public men, and the ministers of religion of every denomination’.

The Southern Cross articles referred to were sourced on Trove (National Library of Australia) by Archives and Record Services.